Shell Fables ~ a Curious Cabinet of Beings & Becoming

This is a film created for the Family Lines project at the Douglas Hyde Gallery in Dublin in June 2022. Salma was invited by artist Alice Rekab to participate in this project and to create her first film. You can read more about this amazing project here https://thedouglashyde.ie/event_cat/family-lines/ and Salma’s film and contribution to the project here https://thedouglashyde.ie/event/salma-ahmad-caller-shell-fables/

My Shell Fables short film also works with ‘artefacts’ of a different kind, from my own past, childhood, my parents pasts. I have been working with these relics, residues and deposits for a few years now but in particular since my mother passed away in 2020. My text/image work Crossing Formations, as part of the book Forms of Migration by Falschrum Books Berlin, was the first major work to emerge that deals with how the political and the personal collide. There are parallels - things from deep time burst out into my present causing potent ripples in space/time. That colonial past isn’t over. It has carried on rippling throughout my life, bringing my parents together but also leaving behind an unresolved sadness and fracture that is part of who I am. There is also accountability and caring about these ‘artefacts’ from our pasts, however quotidian, as they tell us where we came from. They emerge from a deep tomb of shadows, holding within them the same fractures that both separate and hold the ‘body’ together in a living accommodation of ‘conflict’ surrounding identity. I can always see and feel both sides at once.

About the film Shell Fables - Salma Ahmad Caller May 2022

Shell Fables ~ a Curious Cabinet of Beings & Becoming

*A Thing-World ....

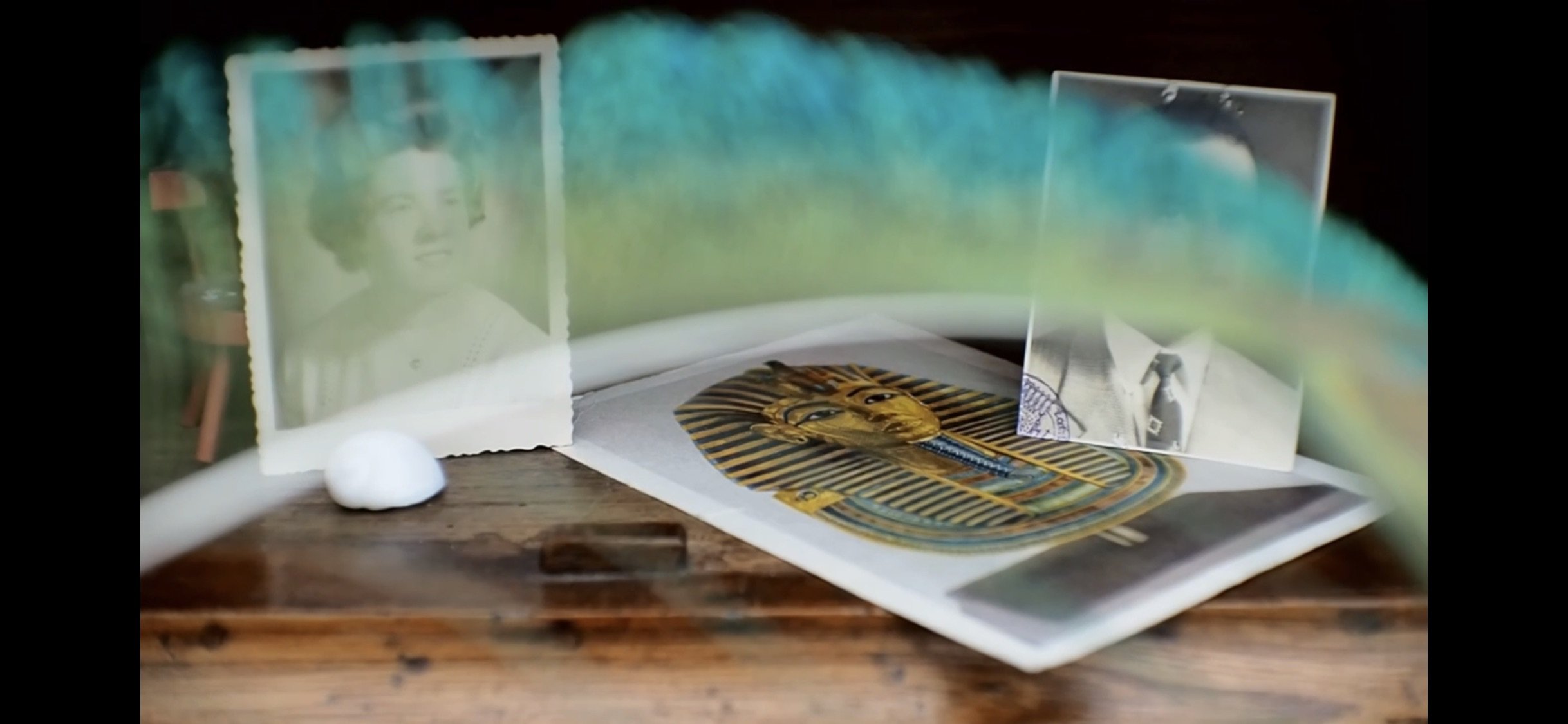

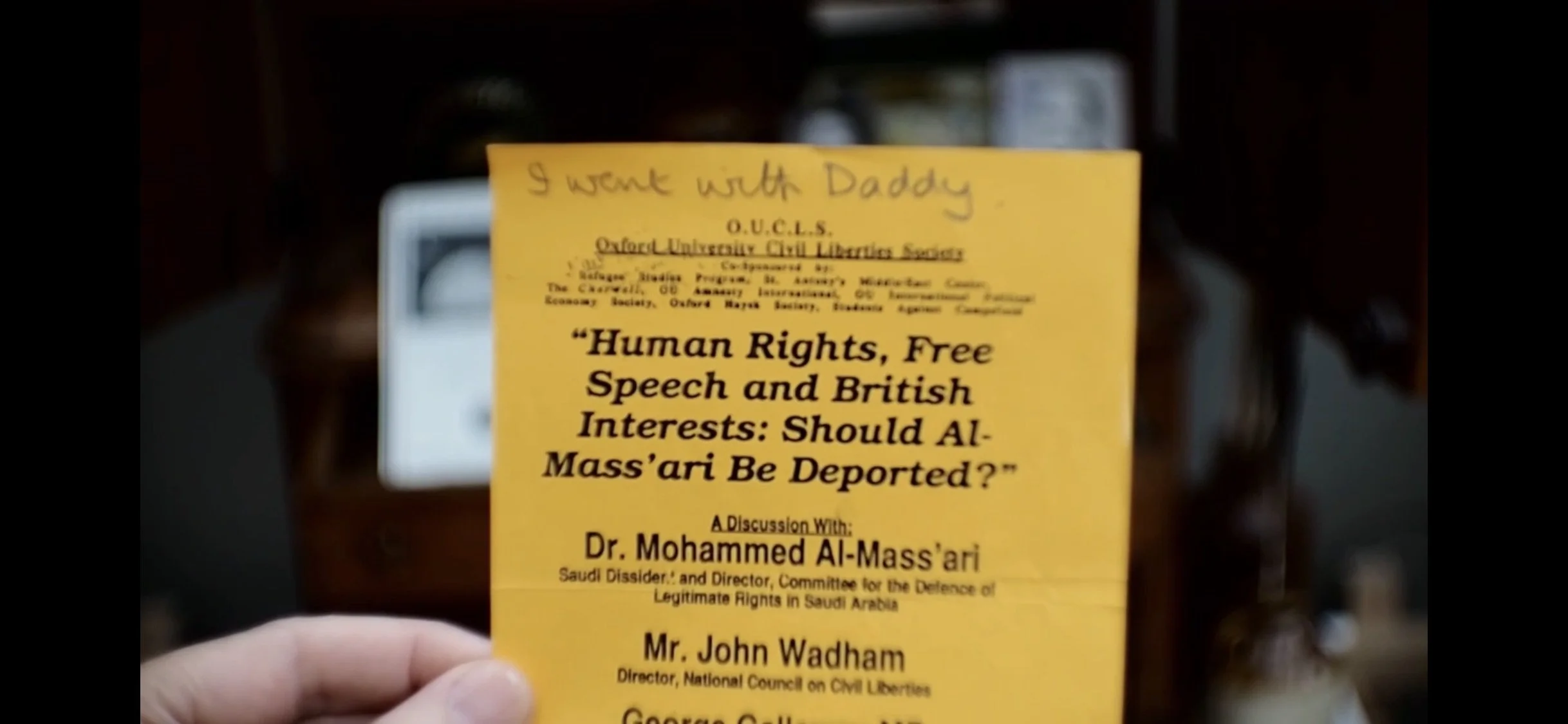

This fifteen minute film is Salma Ahmad Caller’s first film, a prototype, curating her mixed-race identity as curiosity. It is a continuation of her art practice working with personal family archives of photographs and things. These curious Things survived decades of her English mother and Egyptian father’s lives, from Oxford in the 1960s to Cairo where her older sister Hala was born, to Mosul where she was born in 1969, and on to a childhood in Kano, Nigeria, and teenage years in Jeddah and Riyadh in the 1980s. Juxtaposing things that seem to belong to ‘opposing’ cultures creates strangeness and blurs boundaries. These Things are also witnesses to strange and forbidden encounters across divides created by ideologies, imagined and constructed difference, power and desire. The currents of Orientalism, colonialism and Empire moved these small Things in unexpected ways.

The assemblage of ‘fables’ have been filmed ‘on set’ in an antique miniature armoire cabinet from the late 1800s that becomes a miniature stage where the smallest most insignificant seeming things perform, speak, create and transform identity. Evoking early modern curiosity cabinets of wonders and marvels that held objects curated to show the ‘strangeness’ of others, often displaying ‘exotic’ specimens of newly ‘discovered’ worlds and ‘bizarre’ hybrid creatures that spanned the boundaries between categorical types, her own cabinet becomes a metaphorical space to explore her identity as always the Stranger in-between.

Markers used to construct racial identity like eye colour, hair colour and texture are repeating imagery that point to the ways in which societies create belonging and dispossession.

The miniature cabinet full of small Things is also suggestive of a dollhouse, a place once used by wealthier European women to curate self-image, exercise control of the domestic space and to explore her own interiority. The cabinet, the shell and the dollhouse point to interior worlds, to liminal chambers of wondering, becoming, belonging, longing and the desire to know.

The film is a sequence of ‘acts’ where the ‘collector’ curates arrangements of things, and then proceeds to activate them through repetition of various gestures, taking them out of the cabinet, peering closely at them, turning them over and over to experience their materiality and sensuous surfaces and to ponder their meanings. These gestures also evoke the quasi-scientific and philosophical processes of examining strange species under the microscope and questioning their relationship to dualities like ‘body’ and ‘soul’. Shells and feathers are strange residues of what was once both living and non-living.

Reflective surfaces, iridescences, glass and crystals, all create mise en abymes suggesting infinite recurrence, self-reflection and introspection. Eyes are looking, hands are touching and trembling.

Each Thing acting within the cabinet is a disruptive Fragment that can never really be pinned down or catalogued. Any notion of nationality, identity or fixity is constantly disturbed, any attempts to curate wholeness or completeness fails.

* Filmed using a digital camera with a vintage 1970s vidicon lens aperture constant at 2.8 creating a very limited depth of field.

The Night of Counting the Years by Shadi Abdel Salam - As part of participating in Family Lines I had to select film by another director that had a deep impact on me.

The reasons I chose The Night of Counting the Years by Shadi Abdel Salam (originally called The Mummy / al-mummia in Arabic) are several and perhaps unexpected. It was made in 1969, the year I was born and was screened in 2017 by AiM (Africa In Motion) as part of a focus on Africa’s Lost Classics, otherwise it is hard to find. It was one of the first early Egyptian films that I watched in my twenties after having moved to the U.K. and it had a very haunting and lasting effect on my imagination. A feeling of deep time, of the very distant past being present in the now. Itself an artefact carrying the ‘radioactive’ residues of problematic histories of Egypt into our bodies. It gave me glimpses of the landscapes, both real and imagined, political and personal, being created in an Egypt from my father’s youth, and shows how the ancient past, stolen artefacts and the more recent colonial events of that time are so entwined as to become almost invisible. It raises many questions for me, and is full of contradictions. I feel confused when I watch it and also very moved and drawn to an imaginary Egypt that I can never reach, and my father whom I could never really reach.

As the Alex Cinema blog explains, films coming out of Alexandria played a vital role in establishing Egyptian cinema. Alexandrian studios and films were a mixture of Egyptians and foreign residents living there. Shadi Abdel Salam was born in Alexandria in 1930, a few years after my father was born in Cairo. So they were of a similar generation and time. A time of continued occupation of Egypt by the British. This film is unusual in that the script is in Classical Arabic, monumental, solemn, literary, Quranic, rather than in Egyptian dialect. Abdel Salam studied at Victoria College in Alexandria and travelled much in Europe. It always intrigued me that he felt he could only write the script in English. He then had to find someone to translate it back into Classical Arabic. This speaks of how colonisation affects people in such complex ways, and affected my parents and my own life - at a deeply subconscious penetrating level. So from it’s very conception in the director’s mind, it was a hybrid body, like mine, and crossing over within it Egyptian and British cultures and their painful entanglement with each other. So it is a film that raises complicated questions about identity and cultural heritage, not only from within the subject matter but in it’s very formation.

Often Egyptians have been portrayed as backward and not interested in their own Ancient Egyptian heritage, and not able to look after their own - hence it is safer taken away from them and housed in places like the British Museum. Does this film play into that narrative? Abdel Salam felt that Egyptians needed to take their history seriously. But the blame is laid firmly at the door of the tribe in question who are stealing artefacts from tombs from the 21st Dynasty as part of their survival. No questions are raised about the reason this black market for Egyptian artefacts going to European buyers/museums was so lucrative, or the dark manipulative forces of colonialism behind these movements of sacred things. Of course Abdel Salam is taking issue with the Egyptian people themselves, asking them to care about their own history and this is an essential part of the film. It was his mission to make more Egyptians know and care. To what degree did they not care in fact? And it is interesting to note that he has set the film in 1881, on the eve of British colonial rule. At the heart of the the film are torn loyalties and fractured identity. In Europe at the time and even now, there is very little interest in Egypt’s African/black, Islamic and other histories, or rural traditional culture. Egyptomania was all consuming in the 1930s onwards in Europe and America. So for me this film is very close to home in terms of all the conflicts that it reveals, through its omissions as well, across an Egyptian / British divide, and it’s very formation and creation have come out of division/fracture, as have I.

My Shell Fables short film also works with ‘artefacts’ of a different kind, from my own past, childhood, my parents pasts. I have been working with these relics, residues and deposits for a few years now but in particular since my mother passed away in 2020. My text/image work Crossing Formations was the first major work to emerge that deals with how the political and the personal collide. There are parallels - things from deep time burst out into my present causing potent ripples in space/time. That colonial past isn’t over. It has carried on rippling throughout my life, bringing my parents together but also leaving behind an unresolved sadness and fracture that is part of who I am. There is also accountability and caring about these ‘artefacts’ from our pasts, however quotidian, as they tell us where we came from. They emerge from a deep tomb of shadows, holding within them the same fractures that both separate and hold the ‘body’ together in a living accommodation of ‘conflict’ surrounding identity. I can always see and feel both sides at once.